As we saw in yesterday’s post, kids in low-income neighborhoods frequently change schools, but does that help them get into better-performing schools?

In our newly released study of 10 low-income communities participating in the Making Connections initiative, we found that families who moved out of their school district were more likely to switch to a better-ranked school. In fact, it was the most important variable accounting for changes in school performance.

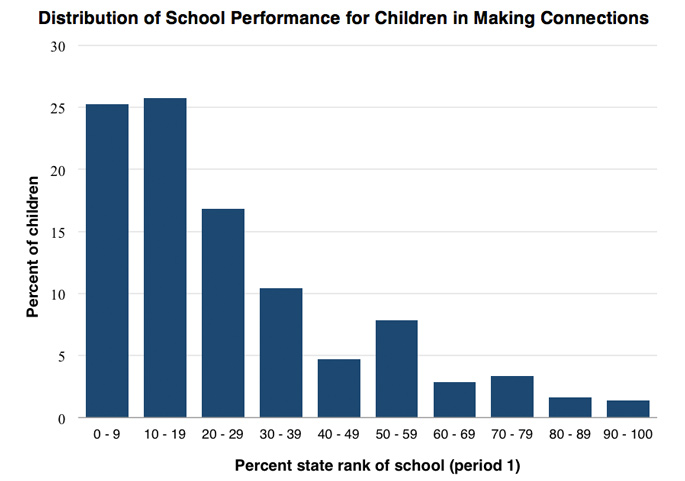

To begin, it’s important to understand that most children in these low-income neighborhoods initially attended strikingly low-performing schools. More than half the children (51 percent) attended schools ranked in the bottom 20th percentile of their state. Changing to a better-ranked school clearly mattered.

Three years after the first survey, we examined school ranks for children with a follow-up survey. School ranks remained largely the same, but the statistics mask some important changes for individual children—in both directions.

- Residential mobility. The most important factor explaining changes in school performance was whether a child moved out of the school district where he or she had previously gone to school. This change was associated with an 8.9 point average improvement in percentile state rank, even when controlling for other factors. Yet children who moved homes within the same school district saw no improvement on average.

- Parents’ education, employment, and finances. Higher parental education was associated with increases in school rank. And financial distress (defined as difficulty affording food) was significantly associated with children switching to worse-ranked schools. Children with an employed parent did no better than children whose parents were not working, however. And household income and housing tenure were not associated with changes in school performance either.

- Racial differences. Relative to white children (and controlling for other factors like initial school rank), black and Hispanic children ended up in lower-ranked schools.

- Age. A child’s age did not predict changes in school rank, nor did whether children made a nonpromotional (e.g. one elementary school to another) or promotional (e.g. elementary school to junior high) change.

- Parents’ satisfaction with school. Parental dissatisfaction with their kids’ initial schools was not associated with their children getting to higher-ranked schools, even though less satisfied parents were more likely to have children who switched schools.

Previous research on the effect of school and residential moves on educational outcomes is mixed, probably due to heterogeneous national or state samples, with many moves being neutral or positive in terms of school quality. Our study affirms that many residential and school moves in low-income neighborhoods do not generally result in children attending higher-ranked schools and can actually lead to the opposite.

Children of families that move relatively short distances in response to financial distress or household compositional changes frequently move to schools that perform the same or worse. It is only when families move outside the originating school district that we see reliable gains in school rank.

In a final post in this series tomorrow, I explore what these findings mean for place-based initiatives, such as Promise Neighborhoods.

This post is the second in a series that showed results from our new study of 10 communities participating in a place-based initiative, Making Connections. The first post showed that residential moves and switching schools were commonplace, but that for many children, these two types of mobility also occurred independently. The third explains how reducing unproductive school and residential churning may be a key to place-based investment success.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.