Several recent press accounts have used figures developed by my Urban Institute colleagues C. Eugene Steuerle and Stephanie Renanne and others by the Social Security Administration to conclude that most Americans now get a raw deal from Social Security. True, these figures show that an average two-earner married couple will collect less in lifetime Social Security benefits than they would have received if they had instead deposited their payroll tax contributions and those of their employers into a simple savings account. But that doesn’t mean the system is broken.

These calculations rely on stylized life histories that don’t apply to most working Americans. For example, some computations assume that each spouse works every year from age 22 to age 64, always earning the national average, and begins collecting Social Security at age 65. For most of us, the reality is more complicated. We generally start out making much less than the average. Many of us, especially women, take time off or work part-time to care for children or other family members. Job loss, injury, or illness sometimes interrupts our careers. Nearly half of us retire at or before age 62. And most wives still earn less than their husbands. Making the two-earner, average-earning career model more realistic lowers estimated benefits somewhat but reduces estimated taxes far more, implying more favorable returns from Social Security for large swaths of the population.

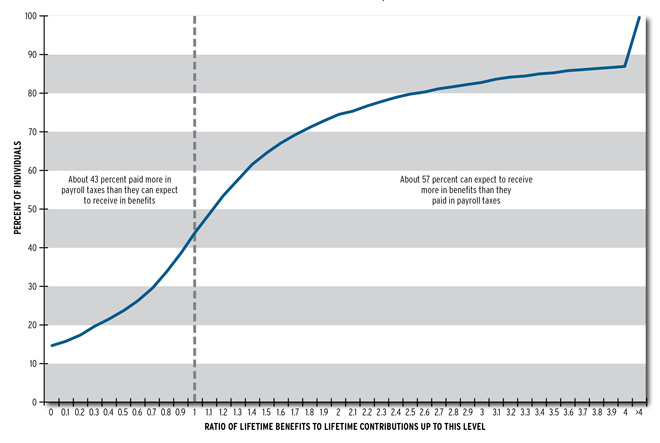

Instead of focusing on hypothetical couples or individuals who aren’t typical of most Americans, consider the projected distribution of Social Security returns from a large sample of earners born in the early 1950s who are now in their early sixties. We see that individual lifetime Social Security experiences vary tremendously. Some people contribute for many years but die before they can collect (so their ratio of benefits to contributions is zero). Others become disabled early in life or live longer than most and so receive far more in benefits than they paid in taxes (pushing their ratio above two).

Cumulative Distribution of Ratio of Lifetime Social Security Benefits to Lifetime Payroll Tax Contributers, 1952-1955 Birth Cohorts

This variability in Social Security returns is a defining feature of any insurance program. But Social Security is a unique form of insurance, providing guaranteed, inflation-protected income for life upon retirement or disability (and, after death, to dependent survivors). It safeguards against risks that are difficult to predict—like experiencing a severe disability early in life or living far longer than average. Affordable, comparable products are hard to find in the private market.

Undeniably, Social Security was a great deal for earlier generations, who were much more likely to live in poverty than current and near retirees. And more workers in the future will get less than they paid in, particularly as the system adjusts to the financial pressures created by the surge of Baby Boomer retirements. But that’s partly because many current and future workers can expect to earn more than earlier generations did. And partly because those workers who are getting less than they paid in will reach retirement age without experiencing a severe disability, will have died too young to receive any benefits, or will receive lower replacement rates because of relatively high earnings. For a majority of the population, Social Security remains a good deal. As we look to improve the program’s funding status in a fair way, let’s focus on maintaining a reasonable distribution of lifetime benefits and contributions, rather than focusing on whether the system looks good for an “average” individual or couple who does not in fact reflect typical Americans’ experiences.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.