According to the College Board*, the 2014-15 increases in tuition and fees across the country were moderate. As usual, the sticker price of a year of full-time study rose more than the Consumer Price Index but as was the case last year, much less than the historical average. Rather than just breathing a sigh of relief, we should ask what this means for students and families, now and in the future.

What happened to the price of higher education this year?

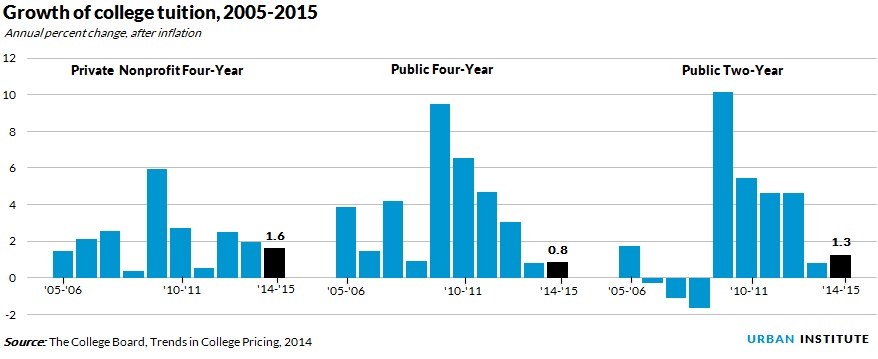

After adjusting for the 2 percent increase in the Consumer Price Index between July 2013 and July 2014, published tuition and fee increases ranged from an average of 0.8 percent at public four-year colleges and universities to 1.6 percent at private nonprofit four-year institutions. The average annual increases in these sectors over the most recent decade were 3.5 percent and 2.2 percent, respectively. And in both of these sectors, the price increases were smaller between 2004-05 and 2014-15 than over either of the two preceding decades.

So college prices are not rising at an accelerating rate. That’s good to know. Concerns that the sharp increases in the recessionary years of 2009-10 and 2010-11 signaled a new and frightening trend turn out to be incorrect.

What about the future?

The moderate news about college prices this year does not mean we should relax. Published prices have been rising faster than average prices in the economy—and much faster than the incomes of most Americans—for many years. Price increases are not accelerating, but they are accumulating.

The average sticker price at public four-year colleges is 3.25 times as high in 2014-15 as it was 30 years ago, after adjusting for inflation. In the public two-year and private nonprofit four-year sectors, the average price is about 2.5 times as high as it was in 1984-85.

To understand how people pay these prices, we need to look at available financial aid. Grants and tax benefits have increased quite a bit and the net prices students and families actually pay have grown more slowly than these published prices.

Nonetheless, it is sobering to put the price increases into the context of income trends. Whether we look at the past 30 years or at the past decade, people at the top of the income distribution have done better than others. Average income for the top 5 percent of US households was $128,200 higher in 2013 than 30 years earlier, an increase of 66 percent after adjusting for inflation.

For the middle 20 percent, the increase was $5,700 (12 percent) and for the lowest-income group it was $400 (4 percent). Incomes at the top were about the same level in 2013 as in 2003, but those lower down the income scale saw their real incomes fall over the decade.

Earnings trends have been much more positive for those with a college education than for those without. For example, median earnings for men with a bachelor’s degree or higher increased by 6 percent between 1983 and 2003, while median earnings fell by 4 percent (after adjusting for inflation) for men with only a high school degree.

Between 2003 and 2013, median earnings for women with a bachelor’s degree or higher fell by 2 percent, while median earnings for women high school graduates fell by 9 percent. The better prospects for those with higher levels of education explain much of the concern about college prices.

Price increases may be moderate for a few years. But unless the historical patterns change dramatically, the next time employment and incomes head downward—leading to pressures on state budgets—funding for public higher education will again fail to keep up with enrollments, endowment values and annual giving to private institutions will decline, and price increases will accelerate.

Although sticker prices don’t really tell us how much people have to pay for college, since most students get grant aid or tax credits or both, some people do pay the full price, and many others are likely discouraged from preparing for and applying to college out of fear of these prices.

Now that price increases have slowed, it’s time to take a step back and think about how we finance higher education in this country and whether our reliance on state funding, which is so influenced by the ups and downs of the economy, is the best way to assure we devote the resources necessary to educate Americans, preparing them for productive and rewarding lives.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.